Godot Recipe: Finite State Machine #2

⚠️ This post assumes you have a basic understanding of Nodes and Scenes in Godot and some familiarity with C# syntax if you plan to code along!

Last time, we left things in quite a mess.

A class overview of our current FSM looks like this:

classDiagram

direction TB

class StateMachine {

+ ChangeState(State) void

}

class State:::italic {

- _name : string

+ Enter() void*

+ Tick(double) void*

+ PhysicsTick(double) void*

+ Exit() void*

}

StateMachine --|> Node

State --> StateMachine

StateMachine --> WalkingState

StateMachine --> IdleState

StateMachine --> State

StateMachine --> Mover

State

WalkingState --|> State

IdleState --|> State

Mover --> RigidBody3D

namespace Godot {

class RigidBody3D

class Node

}

It might not look too bad at this point. If I recall, our demo showcase proved that our basic movement system worked! So why should we bother reworking it?

Once we start adding more systems, more states and (cue foreshadowing) a way for our states to handle external events, this setup will swiftly become a breeding ground for logical errors and hard-to-maintain code.

My pain points at the moment are:

- We’re not using any organizational tools to categorize our classes

StateandStateMachineform a circular dependency- States need to access other states through the StateMachine

WalkingStateneed to accessMoverthrough the StateMachine- Overall, classes are too dependent on concrete classes (tight coupling)

Let’s make a plan to solve this and prevent future headaches!

⚠️ The tips and techniques shown below are workflows and structures I’ve found works well for me. There might be more idiomatic ways to achieve modularity and encapsulation in Godot.

Scope

The goal for this post is to utilize the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) to kill off our circular dependency and make our code more loosely coupled. We will briefly touch on the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) and what it means for our code examples.

We will also be introducing a Locator pattern to improve how states get a hold of systems and other states.

In addition to this, we’ll organize or classes into namespaces to give our codebase some well-needed structure.

We’ll also honour the Interface Segregation Principle, but after that we put a LID on SOLID for now (sorry not sorry).

We’ll end up with something that looks like this:

graph

subgraph FSM

State--implements-->IState

State--has-->ISystemLocator

State--has-->IStateLocator

subgraph Control2[Control]

State

IdleState

WalkingState

StateMachine

IdleState--inherits-->State

WalkingState--inherits-->State

end

StateMachine--has-->IState

StateMachine--implements-->IStateLocator

StateMachine--implements-->ISystemLocator

end

subgraph Motion

subgraph Control

Mover

end

IMover

Mover--implements-->IMover

end

WalkingState--has-->IMover

Mover--has-->RigidBody3D

StateMachine--inherits-->Node

subgraph Godot

Node

RigidBody3D

end

🙋🏼 Not a class diagram, I know – Mermaid doesn’t support nested namespaces in class diagrams yet, but subgraphs in flowcharts kinda does the trick.

We’ve got some refactoring to do, let’s go!

Using namespaces for organization

I like my classes to belong to a well-defined module. To help me enforce this, I use C# namespaces.

I follow a convention where the root namespace is the name of my project, let’s say Project. Publically available interfaces live in a nested namespace called the same as the module, let’s say Project.FSM. Classes that perform logic that is internal to the module live in yet another nested namespace in that module, let’s say Project.FSM.Control for logic.

🙋🏼 If we want to separate logic and data, I would also introduce the namespace

Project.FSM.ModelsorProject.FSM.Data– a Model-View-Controller approach!

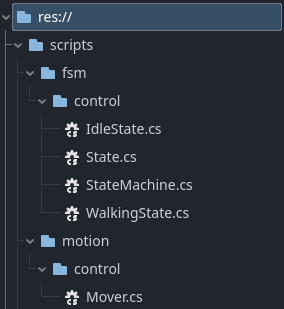

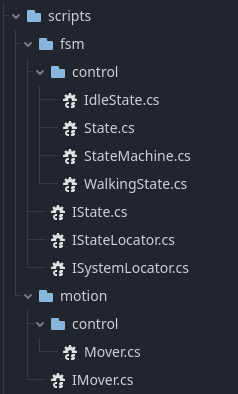

All classes are updated to use this convention. The class-namespace mapping looks like this currently:

- Project.FSM.Control

- State

- IdleState

- WalkingState

- StateMachine

- Project.Motion.Control

- Mover

Optionally, you can mimic the namespace structure in the project folder structure. I always do this.

Following this namespace convention, it shows that all our classes are Control classes and shouldn’t be exposed publically. We’ll sort this out by introducing interfaces as we go along.

Solving circular dependencies using DIP

DIP stipulates the following:

- A high-level class mustn’t depend on a lower-level class

- Abstract classes and interfaces should not depend on concrete classes

- Concrete classes should depend on abstract classes and interfaces

Its goal is to create a more robust and maintainable solution. How does this relate to our current code?

In our current setup, the state is a lower-level class and the machine is a higher-level class. States should not need to know anything about state machines - not even that they exist. In turn, state machines should not care about state details - they should only depend on an abstraction of states.

How do we achieve this? It might come off as a bit esoteric, but it’s not that weird in practice!

Adding Locator and IState interfaces

The states do not need the state machine itself. What they do need is a way to access systems, so they can control aspects of the character controller. They also need to relay WHEN to transition to another state, and WHAT state to transition to.

The way I tackle this, is that I introduce two interfaces: ISystemLocator and IStateLocator in Project.FSM and have StateMachine implement them. The goal here is to keep the fetching of systems and states as generic as possible.

I also introduce an IState interface in Project.FSM, so that our IStateLocator can depend on an interface rather than an abstract class. Similarly, all references to states in StateMachine can instead reference the IState interface

public

public

public

As a matter of fact, we can fully generalize the Locator pattern. I’ll make one general Locator, and one generic one where you can specify constraints. I’ll put them in a namespace called Project.Core. Both ways are viable. This generic one might be a bit overengineered, but I’ll use it for now!

⚠️ This

ILocatordefinition is left out of the class overview at the top of this post. They made the diagram very hard to follow.

The abstract State is updated to implement IState. Concrete State classes are updated to store references to ILocator and ILocator<IState> instead of StateMachine.

Shifting state-changing responsibility to StateMachine

I lied, the LID is officially off as we leverage the Single Responsibility Principle (S).

🙋🏼 You could say it SLID off.

The responsibility to call ChangeState is shifted from State to StateMachine. Since the new interfaces don’t expose the ChangeState function, we instead return the result of ILocator<IState>.Get<T>() to the StateMachine where it can handle state-changing internally. The IState interface is updated to return IState on our tick functions for usual condition checks.

In doing so, StateMachine.ChangeState(State) can be made private. 💡

You could also add an IState return type to Enter if you feel like it, for really early state change guards. I won’t for now!

public

The StateMachine class is updated to implement the Locator interface as shown below. I decide to keep the states inside the StateMachine using a list.

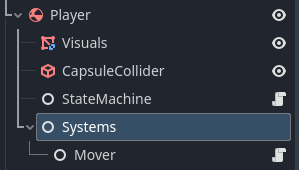

For now, I decide to have all systems under a Node called Systems. We export this and assign it in the Inspector.

using ..;

using .;

using ;

public partial

🙋🏼 Using

OfType<T>from LINQ might not be the optimal way to do state and systems fetching. However, I find it very ergonomic as it allows me to work strictly with types in the state logic. If you have another neat way to solve this, I’d love to hear about it!

Given these changes, we have to move around and refactor our states a bit.

As an example, WalkingState ends up looking like this after the changes:

using ;

using ..;

The StateMachine is updated to handle potentially returned states from the tick functions:

public partial

Finally, make sure the scene structure is updated to respect that systems are expected to be children of the Systems node:

Hitting play should show that the StateMachine works just as before.

🙋🏼 I admit it’s a lot of work for no new functionality, but it should help us do better design choices moving forward and provide us a framework on how to organize our systems.

A brief comment on Liskov substitution

This principle states that you should be able to substitue an object with a sub-object without anything breaking.

By introducing IState and continue using our StateMachine as if nothing changed, we assume (🚩) that our code passes the Liskov substitution test. The machine should accept any object implementing IState and still work as expected. It seems to hold true for IdleState and WalkingState, but we should be wary as our module grows with increasingly complex interactions.

The same goes for systems – next let’s do some abstractions for our Mover!

Loose coupling for systems

We loosened up our coupling by introducing the IState interface. We can do one better and let Mover implement the IMover interface:

public

The states can now also be updated to save references for the systems they need. On construction, WalkingState locates and stores the reference to the IMover.

As shown above, states only need to locate and store the systems as they are constructed.

Therefore, we can do away with the persistent ILocator reference in the abstract State class.

Now this is neat!

Trying out our new architecture

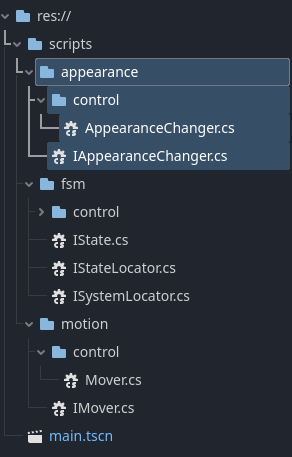

If your folder structure is a reflection of the namespaces, our scripts folder should look rather tidy now.

With this new setup, what does it look like to add a new system? I’ll add a contrived system that changes the Player color and decide that the Player turns blue while idling and red while walking.

The folder structure would hade this added to it:

And this code would be added:

// IAppearanceChanger.cs

// AppearanceChanger.cs

using ;

// IdleState.cs

public partial

Similarly, I locate the Appearance system in WalkingState, and change the color to red – et voilà!

End result

I’ve rambled a lot about software design, which can quickly become dull. If you’ve made it this far – great job!

How did we fare? Did all this nonsense actually solve anything? Let’s address my introductory pain points:

| Problem | Plan | Solved |

|---|---|---|

| Poor code organization | Introduce namespaces | ✅ |

| Circular dependency | Inverting dependency using interface | ✅ |

| Tight coupling for states fetching states | Use Locator pattern for states | ✅ |

| Tight coupling for states fetching systems | Use Locator pattern for systems | ✅ |

| Tightly coupled classes | Depend on interfaces, Liskov substitution in mind | ✅ |

Our states no longer expect concrete implementation to solve our needs.

They simply ask for a reference to any object that fulfills a specific contract – the interface.

🙋🏼 A real neat thing is that we can track dependencies by gauging the

usingstatements in our classes. If we see any Control class use another module’s Control namespace, that’s a red flag now and we’re probably missing an interface.

In the future, I want to take a look at event-handling support in states. This way, polling conditions in ticks won’t be the only way to trigger logic or state transitions in our FSM!

If you’re feeling curious, try your hand at setting it up yourself! ☀️

All the best,

Nilsiker